MONTREAL, SEPTEMBER 27, 2022

Did you know that, from the 1910s, La Guilde worked to ensure the livelihood of the traditional artistic practices of Canadians of all backgrounds by supporting the craftwork of people who immigrated from Eastern and Western Europe alike, as well as from the Middle East? In this article, we delve into La Guilde’s archives to discuss the relationship between art and hospitality.

How did the women of La Guilde mobilize the arts to make Canada land of welcome? This question is relevant as we ponder how the art of diasporas established in Canada was promoted as contributing to the development of national identity in La Guilde’s eyes. We assembled documents from our archives and objects from our permanent collection that retell stories from our last century on the land we now call Canada, and look forward to how the arts can contribute to weaving our intercultural future. Throughout this article, we seek to highlight the resilience of newcomers in early twentieth-century Canada.

*We retain the term "Indian" used to refer to Indigenous peoples in early twentieth-century publications to reveal and better scrutinise contemporary social attitudes enfolded in our archives.

FROM COAST TO COAST: THE COLLECTIVE CONSTRUCTION OF CANADIAN CHARACTER

From La Guilde’s inception in 1906, the women at its helm, Mrs. Alice J. Peck and Miss Martha May Phillips, advocated for the recognition of Fine Crafts, then dismissed from grand movements as the “minor” or “lesser” arts—utilitarian labour lacking the intellectual engagement of painting and sculpture, otherwise known as the Fine Arts (Phillips, Notes 1910). As mentioned throughout the Did you know... series, the women of La Guilde took it upon themselves to encourage the undervalued crafts. In In Good Hands: The Women of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, Ellen Easton McLeod’s book on La Guilde's history, the author underlines how “this lack of support gave women leaders the opportunity to make a difference. They could provide a practical solution by encouraging and promoting women's work in applied arts, home arts, and handicrafts” (1999, 84). Bringing to light and to life our founders’ legacy as patrons and educators means taking a sidelong glance at the art market in Montreal over the first half of the twentieth century and thinking critically about whose creations were celebrated and whose were overshadowed.

Mrs. Peck and Miss Phillips were convinced by the potential of crafts to inform social relations in addition to embellishing homes and everyday lives through the creative process’ aesthetic powers (Phillips, Address to North Bay 1910). In an address she delivered to art clubs in Alberta and British Columbia during one of her many business trips to Western Canada, Miss Phillips wrote of crafts as "[...] thoughts wrought into form by the skilled hand, [and] what a wonderful medium for the transmission of thoughts or feeling is the hand, so responsive, so at one with the brain that the character of the individual is stamped involuntarily upon all his handiwork" (Phillips, Afternoon Talks 1910, 2). Our founders believed that individual expression and national character alike could be discerned in the sophisticated craftwork of Canadians of all origins, from Indigenous basketry and quillwork to French-Canadian hooked rugs to Eastern European embroidery. In another speech to the Vancouver Island Art Club in 1910, Miss Phillips voiced her inclusive vision of the “Canadian” character of La Guilde, then known as The Canadian Handicrafts Guild: “[...] wide as [British] dominion—welcoming all members and workers within its borders—from the Algonquin Indian, to the latest immigrant come to make his new home bringing his heritage of skill to become incorporated with ours” (Phillips, Notes 1910, 1). For La Guilde, art remains a medium for weaving tight-knit communities—a means for people from all walks of life to communicate and foster mutual respect.

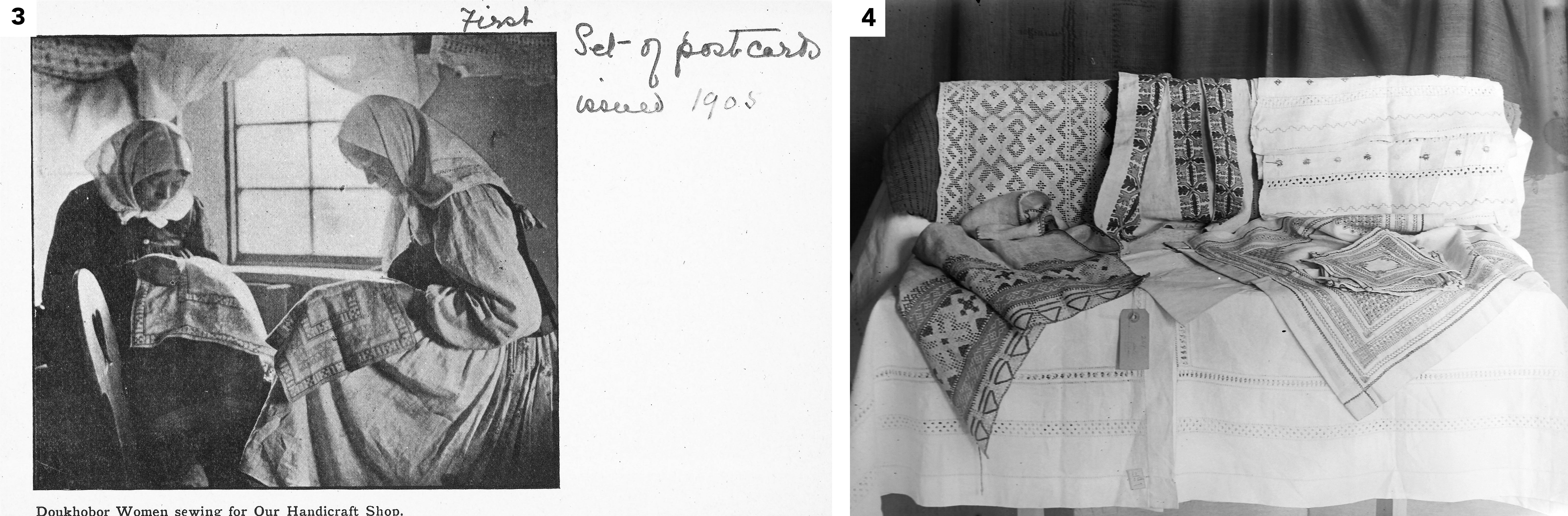

“Self-Help, Not Charity”

Both of privileged status, Mrs. Peck and Miss Phillips were raised with the belief that their position entailed a responsibility to serve those less fortunate than themselves through charitable endeavours, with particular efforts to assist women, Indigenous people, newcomers to Canada and people living with disabilities (Easton McLeod 1999, 234-235). Their unselfish aims were motivated less by charitable inclination than by the will to create economic opportunity for new settlers who would otherwise establish themselves in Canada with a greater deal of hardship. To Miss Phillips, the triumph of crafts had national potential: “[...] success, to us, [means] increased payments to workers, increased usefulness to the individual, increasing independence, comfort and content, and so increasing prosperity in the Country” (Phillips, Notes 1910, 9). With the motto “self-help not charity,” they operated “[...] rather [as] a prevention of charities—a charity in the truest sense” (Phillips 1910). It is in this optic that they sought both to showcase and foster the diversity of Canada’s artistic heritage. La Guilde notably advertised its stimulation of craft industries run by new settlers in promotional materials featured on ships sailing to Canada, and corresponded with government officials to learn about the craft skills of people who recently immigrated (Easton McLeod 1999, 234-235). We are again astonished by our founders’ savviness in promoting craftwork’s potential to bolster personal finances and spur national development, both for potential makers and buyers.

Beyond crafts’ promise of economic development, Miss Phillips trusted their potential to foster solidarity between people of diverse backgrounds, beliefs, and experiences: “Across this wide continent we do indeed need every means to keep us in touch with one another - not by ignoring others of other traditions to whom we have opened our door but by joining hand to hand [...] to pass on from East to West the warm pressure of good fellowship” (Phillips, Address to North Bay 1910). In reading Miss Phillips' writings today, we are aware of the imperfections of our ancestors' actions by La Guilde's present standards. Still, we remain impressed by the inclusive sentiment of her message. Its core values of curiosity, openness, sharing, and collaboration are those that we choose to take with us into the future, those that continue to inspire La Guilde’s mission. As McLeod states, “[La Guilde] sought recognition for the ethnic arts and welcomed these immigrant groups as cultural assets to Canada” (Easton McLeod 1999, 234-235). In Mrs. Peck’s own words, “[...] it has never been the aim of [La Guilde] to make money, but to put money in the hands of both native-born craftsmen and new settlers who without encouragement might not be able to carry on their crafts, so missing the contentment of doing fine hand-work and the joy of self-expression which every human being desires” (Peck 1926, 6).

The Ruthenians and Doukhobors

The earliest correspondences with specific ethnic groups newly established in Canada recorded in our archives hail from the turn of the twentieth century, just predating The Canadian Handicrafts Guild’s incorporation (1906) as a nonprofit organization. Miss Phillips first ventured to Western Canada in 1910 to maintain professional relationships with communities of makers, study their methods, and acquire their artwork. At a time when it was still particularly perilous for a woman to travel unchaperoned, the fact that Miss Phillips undertook this journey alone reminds us of our founders’ fearless commitment to their mission.

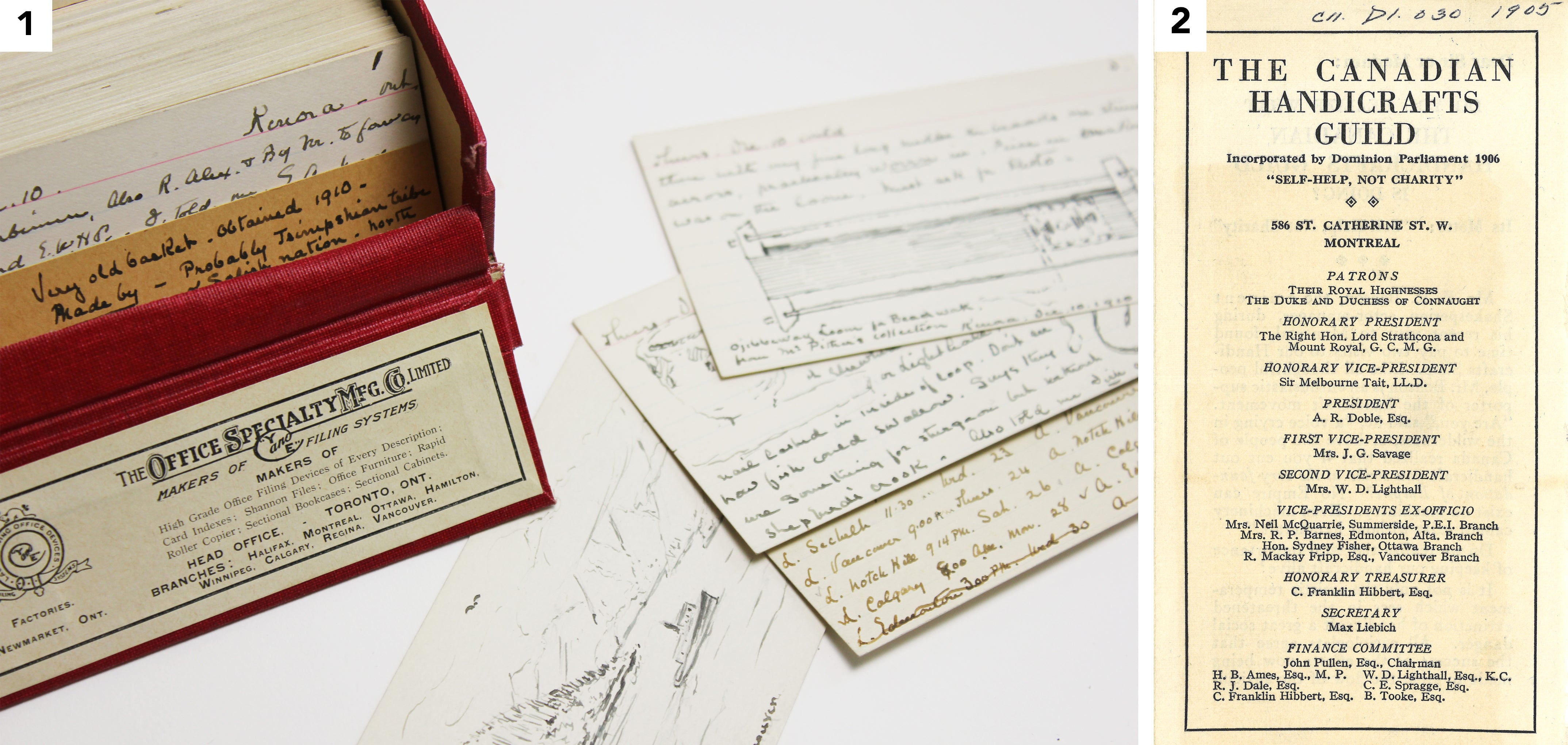

In her diary (fig. 1), Miss Phillips retells a visit to a Ruthenian settlement, drawn from a diaspora of Eastern Slavs native to modern-day Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Belarus. She writes of driving “across miles of rolling, wooded prairie” in below-freezing weather to be warmly welcomed by the priest, nuns, and community. Miss Phillips was touched by their friendliness—sharing hot meals of mutton cutlets and cabbage soup, kissing each other’s hands and wrapping her in blankets on a sleigh ride to witness their craftwork (Easton McLeod 1999, 235-236; Phillips, Memoranda 1910). Though this article aimed to emphasize La Guilde’s welcome of newcomers to Canada, this episode demonstrates the reciprocality of hospitality and intercultural exchange. Miss Phillips was particularly impressed by Ruthenian embroidery on linen woven by hand, from their own flax crops. She even subsidised a prize at the convent for the best pieces produced by the nuns. She commissioned their work and promised to secure loans for them via their husbands and the parish priest, Father Kryzanovski—at the time, laws that discriminated on the basis of sex prevented women from administering their own finances. This allowed them to construct more looms and enabled a greater number of Ruthenian settlers to practise their craftwork (Phillips, Memoranda 1910; Phillips, Western Trip 1911, 4). Other representatives of La Guilde, Madeleine Bottomley and Christine Steen, followed in Miss Phillips’ footsteps to uphold their agreement and assist the artists’ ambitions. La Guilde was concerned with the aesthetic and material quality of the output; Bottomley encouraged a return to artisanal rather than artificial dyes and exclusive use of home-grown linens rather than factory-made cotton even though these processes required more resources. La Guilde also urged the transmission of traditional craft methods to the younger generation by sponsoring Father Kryzanovski and the nuns to run an embroidery class for local Ruthenian children (Easton McLeod 1999, 235-236).

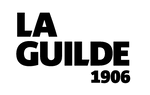

Another early cause championed by the women of La Guilde was that of the Doukhobors (fig. 3), a pacifist religious group exiled from Russia for a cult deemed heretic by the Orthodox Church (Easton McLeod 1999, 99-100). Their arrival was a nationwide concern, and the Industrial Committee for the Encouragement of Doukhobor Home Industries was even formed as a federal initiative to sell work from Doukhobor women across Canada. Edith Watt, La Guilde’s shopkeeper at the time, notably held a lucrative sale of Doukhobor work at her home in Montreal’s Golden Square Mile. Such exhibitions typically sold out, and Ruthenian and Doukhobor craftwork (fig. 4) was well received. In 1913, local journalists celebrated the “eye-catching” and “[...] wonderful hand-woven linens embroidered in the bright colours and geometrical designs so much favoured by these people” (The Gazette 1913; Montreal Star 1913).

La Guilde persisted in showcasing Eastern European creations in its annual exhibitions through the 1930s. Many shows were run in exclusive locations, such as the Windsor Hotel, granting the cause visibility at the price of highlighting the rift between the social classes of the artmakers, and those promoting and selling their creations (Unknown Newspaper 1938).

Preserving Ukrainian Heritage Techniques

This beautiful red and black embroidery (fig. 6-7) from our permanent collection displays characteristics typical of the Ukrainian lowland provinces of Podolia and Polisia, where these colours were favoured in geometrical arrangements. Cross-stitched pieces, like the lowermost yellow, blue, and red cloth, however, would correspond to traditions emanating from the northern and northwestern principalities of Poltava and Volyn. The eight-pointed star, a widely popular motif, would be adapted from broader Byzantine roots. Though our records cannot confirm the provenance of the needlework techniques used in embellishing these particular textiles, our research inclines us towards this interpretation. A program from the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada indicates that most Ukrainian artisans remained true to local traditional designs, for the country did not know the industrialization and rural exodus Canada did over the nineteenth century. The Program stressed the importance of preserving Ukrainian heritage techniques and the singularity of local know-hows: “with the passing centuries, [Ukrainian crafts] developed characteristics which differentiated them from those of any other race. This development took various forms, depending on the situation of the country, the circumstances under which the peasants live, and the artistic temperament of the people. Thus Ukrainian embroidery can be divided into definite territorial groups, taking into account colour, design and technique” (Handicrafts Program, 6-7).

Supporting Polish artistic heritage

La Guilde also aided Polish immigrants in their resettlement in Canada following the German invasion of their home country at the start of the Second World War. La Guilde was invited to show craftwork from Montreal’s Polish community at an exhibition organized by the National Gallery in Ottawa, to support the Polish cause and to demonstrate the survival of their artistic heritage in the face of its devastation. The display of crafts was set to complement artworks by renowned Polish artists “to focus wider attention on the cultural part of Polish national life.” The National Gallery was pleased to exhibit “work of Polish character produced in Canada” or “Polish handicraft work brought to Canada,” and equally open to contemporary work derived from Polish tradition which might “[...] illustrate how Polish hand-craftsmen have adapted themselves to their new environments,” their ability, and ingenuity (Letter Russell 1942).

The chairwoman of La Guilde’s Exhibitions Committee, Mrs. F. M. G. Johnson, immediately consulted the Polish general consul in Montreal, Mr. Jan Pawlica, in the hope of scouting artists who would contribute to the show (Letter Drummond 1942). They attended the Easter Bazaar of Polish Ladies Handicrafts for the Benefit of the Polish War Fund (fig. 10), held by The Polish War Refugees Association of Montreal. La Guilde was ultimately obliged to refuse the National Gallery’s request because its representatives could not source the number of pieces required to fill the space (Letter Drummond 1942; Invitation 1937). La Guilde’s secretary at the time, Helen I. Drummond, explained to Ottawa that “[...] the majority of [the Polish diaspora in Montreal] had come to this continent following military and political oppression and that they had little opportunity to bring household or family treasures” of exhibition calibre (Letter Drummond 1942). The ultimate absence of home crafts from this exhibition would have spoken volumes on war’s potential to dislocate and destroy.

It is mentioned that Mr. Pawlica also chaperoned the immigration to Canada of Ms. Blaszkiewicz—a Fine Crafts teacher—to run courses and workshops for Polish crafts in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, in addition to selling her own work at La Guilde (Correspondences 1937). Other than letters exchanged between committee members, little information on these events remains in our archives. Though our records are sparse, we recognise the importance of these discussions as efforts to provide resources and knowledge-sharing opportunities to those wanting to import their crafts in Canada.

Presenting Crafts at McGill University

The women of La Guilde remained adamant about educating themselves and the public about the traditional crafts specific to each immigrant community when 1.2 million new citizens arrived in Canada over the course of the 1920s. Over the years, La Guilde worked with a variety of immigrant communities and their corresponding diplomatic representation in Montreal. In 1926, Mrs. Peck invited speakers from those consulates to give illustrated lectures on their national crafts. La Guilde partnered with McGill University to present the sessions on campus, free of charge, allowing for a wide audience to attend. Describing the events, McLeod writes that “[...] formal dress was usual at these evenings, and with many classes in French, the series was obviously designed to appeal to an educated, bilingual elite in Montreal society” (Easton McLeod 1999, 236-237). After the success of the first talks on the Crafts of Yugoslavia, Czecho-Slovakia, Poland, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Italy, the course was renewed for another year, featuring the Crafts of Finland, Hungary, Romania, and Sweden, as well as on The Canadian Handicrafts Guild and the arts of Canada.

Mrs. Peck articulates the intercultural aim of the lectures, “[...] planned to inform the public with regard to the arts and crafts of the countries from which Canada [was] receiving immigrants, so that we might be prepared to conserve their knowledge and skill for Canada” (Peck 1929). It is on such an acknowledgement of the mutual exchanges that occur upon cross-culture encounters that Mrs. Peck and Miss Phillips wished for the diverse populations of their country to find solidarity. In addition to bearing in mind this idealistic aim, Mrs. Peck emphasised the practical importance of this education as one through which to “[...] gain a real insight into the abilities of our New Settlers and find out ways and means to be of use to them during the time when they most need our help” (Peck 1929). We are ever in awe of our founders’ sense of entrepreneurship and its application to public service in the name of openness and the aim of social cohesion.

The Education Committee

From its earliest days, La Guilde acknowledged how the intergenerational transmission of traditions can be at once a manual, political, social, and spiritual gesture of knowledge transfer. Especially in the context of diaspora, La Guilde prioritized perpetuating this unique muscle memory. In 1921, fifteen years after launching La Guilde alongside Mrs. Peck, Miss Phillips channelled her educational background to establish La Guilde’s Education Committee. Before co-founding La Guilde, Miss Phillips had indeed acquired a great deal of experience as an art educator at Montreal’s School of Art and Applied Design (SAAD), formally known as the Victoria School of Art, where classes included woodcarving, oil painting, design, ceramics, and many more arts. Though Miss Phillips began her career as an instructor, she quickly rose to the rank of co-principal before being trusted with sole leadership of the institution by 1895. With similar goals to those of La Guilde, SAAD’s practical pedagogy was designed to suit the demands of the art industries and crafts. Miss Phillips trained her students for employment in the same feminist spirit that drove La Guilde’s mission of assisting women in professionalizing their craft and granting them a level of financial independence (Easton McLeod 1999, 31-46).

The Education Committee was dedicated to running classes that taught children of immigrants methods of weaving and embroidery typical of their family’s native country (Annual Report 1930). In 1922, classes pertaining to Jewish-Russian, Greek, Syrian, and Italian customs were given weekly. Working to curb the effects of acculturation, the Committee hired instructors from the corresponding community to teach each class and ensure its cultural legitimacy. It also made sure to “research authentic designs, borrow samples, and investigate how similar work was conducted in American and European cities. By 1923, 231 children from various communities had enrolled in classes at La Guilde (Easton McLeod 1999, 236-238). The Education Committee's cultural sensibility and drive for inclusion worked to accomplish their mission of providing a space for all people to gather, exchange, and make a living from their craftwork.

Many materials for the classes, such as Canadian linens, were provided by La Guilde. Other fabrics, however, like Florentine linens for the Italian class, were expensively imported from Europe. When the time came to find premises on which the classes could take place, the Education Committee looked to rent spaces free of charge, like schools and churches. The women of La Guilde proved themselves to be resourceful ambassadors in times of need, often organizing fundraisers in the form of high tea at one of the members’ homes (Easton McLeod 1999, 237-238; Letter Wolff 1924).

The children’s most successful pieces were included in La Guilde’s annual exhibitions (fig. 12) alongside the adult members’ work. Journalists covering these events, which first took place in the Art Association of Montreal’s galleries, spoke of the exhibition as “a better showing than in any previous year,” and paid attention to the children’s creations as testaments to “how well immigrant children be got to preserve much of their national feeling in their work” (The Star 1931). Profits from the exhibition were divided between the children and the Education Committee, this reinvestment funding the purchase of equipment for the following year’s classes. In 1930, sales of the children’s work at the exhibition totalled 203.44$ [about $3,381 today]. From the age of fifteen, the most promising students were encouraged to become members of La Guilde and start selling their work at the shop (Easton McLeod 1999, 167-169; Montreal Star 1930). This provided many young women with a way to earn their own money in an otherwise patriarchal economy. We are truly impressed by the level of skill demonstrated in the children’s work.

Today, as the arrival of Ukrainian immigrants fleeing their war-torn homeland is a pressing political matter, we felt it appropriate to mobilize archives from our documentation centre and objects from our permanent collection to highlight the history of Ukrainian and Eastern European fine crafts in Canada, and tell stories of artistic resilience. La Guilde is proud to continue showcasing the fine crafts of newcomers to Canada, and contributing to their cultural radiance.

Sydney Guy / Katherine Lacroix

Gallery, Exhibitions and Cultural Activities Assitant / Archives Assistant

With the collaboration of Audrée Brin, Genevieve Duval, and Colin Jobidon-Lavergne.

REFERENCES

- “Annual Report of the Educational Committee”, Montréal, January 20, 1930. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Correspondences between Mr. Jan Pawlica (Consul General of Poland) and Mr. E. A. Corbett (The Canadian Handicrafts Guild’s President), December 1937. Polish Committee, 1937. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Easton McLeod, Ellen. In Good Hands: The Women of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild. Carleton, ON: Carleton University Press, 1999.

- “Handicraft Classes Hold Sale of Work: Articles of Native Design by Girls of Foreign Parentage.” Montreal Star, Thursday, 8 May (1930).

- “Handicraft Exhibition Open: All Parts of Canada Contribute to Collection at Arena.” The Gazette, Sunday, May 25 (1913).

- “Handicrafts Guild Makes Good Display at Art Association.” The Star, Monday, October 19 (1931).

- “Handicrafts Program of the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada,” sans date. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “Invitation to the Easter Bazaar of Polish Ladies’ Handicraft for the Benefit of the Polish War Fund”, Polish War Refugee Association of Montreal. Polish Committee, 1937. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Quebec.

- Letter by Deane H. Russell (Inter-Departmental Committee on Canadian Handicrafts’ Secretary) to Helen I. Drummond (The Canadian Handicrafts Guild’s Secretary), February 28, 1942. C14 D1 062 1942. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Letter by Diane R. Wolff to Miss Phillips, January 24, 1924. Educational Committee, 1924. Educational Committee. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Letter by Helen I. Drummond to Deane H. Russell, March 2, 1942. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Letter by Helen I. Drummond to H. O. McCurry (National Gallery of Canada’s Director), March 26, 1942. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Peck, Alice. Sketch of the Activities of the Handicrafts and of the Dawn of the Handicraft Movement in the Dominion. Montréal: Canadian Handicrafts Guild, 1929.

- Peck, Alice J., The Canadian Handicrafts Guild and the “New Settler”, 1926. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Phillips, Martha M., "Address Used on Afternoon Talks and on Western Trip 1910," 1910. C11 D1 051 1910. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Phillips, Martha M., “Address to North Bay in Normal School,” December 11th, 1910. C11 D1 051 1910. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Phillips, Martha M. “Notes for Address Before Vancouver Island Art Club in Victoria,” 15 November 1910, 5. C11 D1 051 1910. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Phillips, Martha M., “Memoranda & Diary: Western Trip” 1910. C11 D1 050 1910. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- Phillips, Martha M., “Report of Western Trip,” 1911. C11 D1 051 1911. La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

- “Ukrainian Art Shown: Display Here Intended to Encourage Native Crafts.” Unknown Newspaper, Monday, April 11 (1938).

- “Unique Exhibition of Canadian Handicrafts.” Montreal Star, Saturday, February 22 (1913).

IMAGES

(1) Photo of insert cards from “Memoranda & Diary: Western Trip”, 1910. Miss Phillips Travel Diary.(2) “Self-Help, Not Charity” Pamphlet, 1905. C11 D1 030 1905.

(3) “Doukhobor Women Sewing for Our Handicraf Shop” Postcard, 1905. C11 D1 028 1905.

(4) Photo of “Doukhobor Embroderies,” 1905-1908. Glass Plate Negatives.

(5) Ukrainian Cross Stitch Designs from the Collection of the Ukrainian Women’s Assocoation of Canada.

(6-7) Photographs of works from our permanent collection: Red and black Hungarian embroidery with fringe on three sides (E7, E9); Embroidery of a hood (E10); Table runner (E24), early 20th century.

(8) Photograph of an educational work from our permanent collection: Embroidery with 11 pre-printed jute squares (E5), early 20th century.

(9) Letter by Deane H. Russell (Inter-Departmental Committee on Canadian Handicrafts’ Secretary) to Helen I. Drummond (The Canadian Handicrafts Guild’s Secretary), February 28, 1942. C14 D1 062 1942.

(10) Invitation card to the “Easter Bazaar”, 1937, and other documents from “Polish Committee, 1937” and “Educational Committee, 1929.

(11) Photo of Syrian Class, Syrian Methodist School, February 8, 1926. Educational Committee, Photographs Ethnic Classes 1926.

(12) Photo of “Annual Exhibition of Children’s Work (English, Italian, Russian, Greek), 1926, C11 D3 209 1933.

(13) Photo of Greek and Armenian Class, University Settlement, February 6, 1926. Educational Committee, Photographs Ethnic Classes 1926.

© La Guilde, La Guilde Archives, Montreal, Canada.

Je trouve les textes très instructifs et élégants, mais la définition des caractères dans le gris auraient avantage à se noircir pour avantager la lecture, Commentaire strictement technique, merci .

Leave a comment